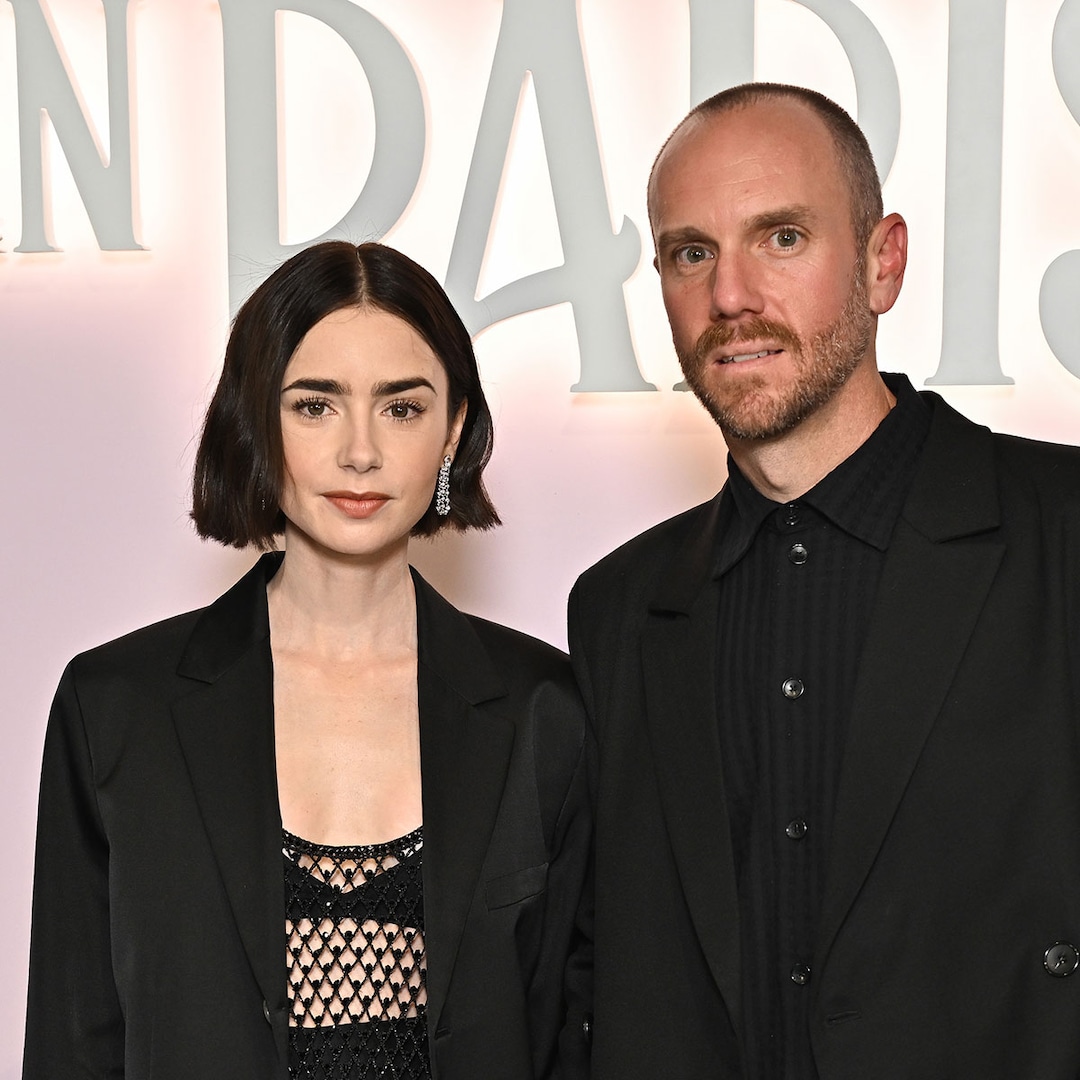

Photo caption: An image of a wildfire in Beauregard Parish from drone video taken Saturday, Aug. 26, 2023. Photo courtesy Louisiana State Police.

Jeff Parker stayed inside his St. Roch home as much as possible the last week of August, as people all around New Orleans reported smelling smoke in the air.

Weather forecasts reported that smoke drifted into the city’s atmosphere from southwest Louisiana, where wildfires were scorching parts of Beauregard Parish. Air quality monitors around New Orleans detected levels of air pollution higher than standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency as smoke blanketed the city. The air quality was so poor that the local office of the National Weather Service recommended that people with respiratory issues, like Parker, remain indoors. “I have allergies that cause me problems all of the time,” Parker said, “but it gets exacerbated when the air quality is that bad.”

When there’s poor air quality, Parker is more likely to sneeze and has trouble breathing, he said. And it probably isn’t just him, as researchers have found links between poor air quality and increased incidence and exacerbation of asthma and allergies.

The recent smoky air was a preview for Parker and other New Orleans residents of a future with stronger, more frequent wildfires, and heightened health risks to accompany them. Experts told Verite that wildfires like the ones being seen across the state — and the harmful air quality the smoke from them produces — will become more common due to climate change. And people with certain health conditions and other vulnerable populations, like communities of color and impoverished communities, who are more likely to have respiratory illnesses than white or affluent people, will feel the brunt of the effects of these disasters.

Rubayet Bin Mostafiz, a researcher at LSU AgCenter who has studied future wildfire risk in the state, said that extreme heat and persistent drought means Louisiana could see more wildfires like the hundreds that have already burned in the normally wet state this summer.

According to research from Mostafiz and his colleagues, Louisiana’s wildfire risk is projected to increase by 25% and property damage loss from these fires is projected to increase to over $11 million by 2050. And that’s a conservative estimate, they said.

And where there’s fire, there’s smoke.

Heather Alexander, an associate professor of forest and fire ecology at Auburn University, who was not involved in Mostafiz’s study, said that for large population centers like New Orleans, smoke is the primary threat posed by increased wildfires in rural areas.

Smoke is especially problematic for people with health issues like asthma, bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and for those with compromised immune systems, she said: “Smoke often accompanies days with high heat, making the human health problem worse.”

Dr. Susan Gunn, a pulmonologist at the Ochsner MD Anderson Cancer Center, said that when people with underlying respiratory issues breathe in smoke, it can trigger wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath and chest tightness. When she smelled the smoke on Aug. 27, she immediately thought of her patients.

“There was just this overlying haze over the city … and I mentioned to my daughter that I knew that my patients would have trouble breathing,” Gunn said. She said she works with her patients to develop a plan to keep themselves safe when there’s poor air quality, which can include carrying a rescue inhaler and staying inside as much as possible.

The public should monitor the news and weather websites for air quality updates, stay inside when there’s poor air quality and wear a mask if they need to be outdoors when there’s smoke in the air, she said.

The smoke that came from the Tiger Island and Highway 113 fires in southwest Louisiana stuck around the New Orleans area for a few days, but future wildfires could produce smoke that lingers in the air for much longer. Other parts of the United States, like San Francisco and New York, have already experienced elevated levels of smoke from wildfires that reduced air quality for several days at a time, forcing residents to shelter in place in recent years.

“There’s really no normal expectation of how long smoke will stick around, because it really does come down to what are the wind conditions on each given day,” said Danielle Manning, a forecaster with the National Weather Service’s New Orleans/Baton Rouge office.

So wildfires — expected to become more intense and more likely in the future due to climate change — will produce more air pollution, creating a dual threat that adds to an already dangerous summertime cocktail of drought, hurricane risk and extreme heat. And hurricanes themselves can lead to reduced air quality, according to Kimberly Terrell, a research scientist with the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, who pointed out that hurricane damage at chemical plants can also result in industrial fires.

Although these ecological disasters tend to affect an entire community, they cause more harm to vulnerable populations, like communities of color, people in poverty, people living outside and people living with disabilities. Terrell said that Black communities are likely to be the most affected by poor air quality from wildfire smoke.

“Think of it like a bathtub … the bathtub is almost empty in the white communities and the bathtub is almost full in the Black communities,” Terrell said. “When you pour a gallon of water into both, you’re going to be okay in the white communities, but in the Black communities, you may kind of get past that threshold where we start to see even more health impacts.”

This article first appeared on Verite News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

e

English (US)

English (US)