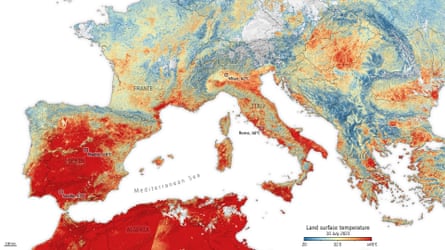

In a world that’s learning how to deal with higher temperatures and more frequent hot spells, experts are debating whether we should name heatwaves in the same way we name tropical storms. The discussion was brought to the fore in Europe this July, when the name Cerberus – unofficially given by a private Italian weather service to the heatwave on the continent – quickly went viral. Its popularity highlighted important unresolved questions – as to who does the naming, what the threshold to name an event is, and what the larger strategy behind the naming is – that, in comparison, took decades to settle for storms.

When a storm’s wind speed passes 39 mph (63 km/h), it is given a name from a predetermined list that countries from the relevant region have compiled. The most severe of these events are known as hurricanes near the Americas, typhoons in the north-west Pacific and cyclones in the Indian Ocean basin and south-west Pacific.

“With tropical storms, we rank them on a severity scale that is well recognised,” says Dr John Nairn, a senior adviser on extreme heat for the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). “We haven’t got there with heatwaves, although we want to get there very quickly.”

Naming a tropical storm is only a part of a complicated risk reduction system, led by the WMO, that includes forecasting when a storm might hit, what citizens need to know, and how they should prepare. The organisation assigns names to avoid confusion and ease coordination. Nairn and the WMO believe naming heatwaves without this larger framework might put focus on the wrong issues and draw attention and resources away from implementing heat warning systems and responses to protect the public.

Instead, Nairn argues, the focus should be on developing an internationally agreed intensity ranking the public can recognise – just as people living in hurricane-prone areas know that a category 5 is more severe than a category 1. He is working to develop such a classification system.

While most people in Europe were calling the heatwave Cerberus, a group of experts and city planners in Seville, Spain, dubbed it Xenia Sevilla. This was part of the city’s pilot programme to name heatwaves, backed by the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center (Arsht-Rock), which is linked to the US thinktank the Atlantic Council. The classification system, launched in 2022, is for now applicable to Seville alone, with names considered when hot conditions reach category 3, the highest level, for three days (it is a five-tier system, with categories from 0 to 3 and an additional no-warning category).

“It’s really important that the name be tied to a specific methodology,” says Kurt Shickman, the director of extreme heat initiatives at Arsht-Rock. “Naming a heatwave because it’s hotter and people are talking about it isn’t as important as having a name when you clearly see it’s going to be dangerous for human health over a certain series of days.”

Arsht-Rock has a wider heat resilience programme that includes working with cities such as Athens, Miami and Freetown to appoint heat officers and prepare for extreme heat, but it has clashed with the WMO – which represents national meteorological organisations – on naming heatwaves. In a technical paper prepared by a WMO meeting in October 2022, the organisation addresses a “recent civil society effort originating in the United States” to name heatwaves, and argued that rushed naming could create confusion among the public and interfere with official and established warning systems.

This summer’s heatwave garnered at least three names: Cerberus, Xenia Sevilla and Cleon, as the Greek, Israeli and Cypriot meteorological services jointly called it. While Shickman says the popularity of the names points to the public’s appetite for them, he agrees international coordination is necessary.

“While naming things can help raise public awareness, I haven’t seen any evidence that examines the extent to which naming extreme events has helped preparedness,” says Dr Chandni Singh, a lead IPCC author and senior researcher at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements in Bengaluru, adding that whether to name heatwaves is not a conversation she has heard in Asia.

Indeed, there is little research on whether naming extreme weather events helps or not. “Partly this comes down to the nature of the work, a combination of meteorology, psychology and communication studies,” says Dr Andrew Charlton-Perez, professor of meteorology at Reading University. “It can be quite hard to build teams that contain all of this expertise.”

Charlton-Perez and colleagues analysed the public’s reaction in 2017 to Storm Doris, which was named as part of a pilot scheme by the British and Irish meteorological services, later made into a permanent programme. He says that naming the storm meant “there was increased public awareness of [it] before it affected people in the UK and particularly during and after it arrived”.

A similar study by scientists at the National Observatory of Athens (NOA) also suggests that storm-naming is connected to better awareness, explains Dr Vassiliki Kotroni, the research director at NOA. “We found that there was a very high acceptance of the storm-naming, and explicitly in those people who have been affected by a named storm.”

Why would names have this effect? Some point to our social brains. The neuroscientist Dr Kris De Meyer, director of the Climate Action Unit at University College London, explains that human brains are well suited to thinking about the mental state of others as well as ourselves, a process called mentalising.

De Meyer says this happens in areas of our brain that also operate a powerful memory system (separate from the one we use for raw memorisation) that is tailored to social information, such as names. “Psychologists have termed this extra memory strength for social information the social encoding advantage,” he says. “Naming a storm or a heatwave could be the first step towards activating the mentalising network and therefore triggering the social encoding advantage.”

Heatwaves are becoming stronger and more frequent because of global heating. For example, the prolonged heat experienced in India and Pakistan in early 2022 was made 30 times more likely by human-made climate change. The question for policymakers and scientists is: what can help us prepare better? The changing climate is already forcing meteorologists to adapt their practices: with storms occurring more frequently in the North Atlantic, the committee in charge of naming them has stopped using the Greek alphabet as backup once it uses up its regular list of 21 names for the year, and will instead use another, secondary list.

Nairn argues that finding an international agreement on heatwave categorisation and naming won’t be quick, as there is not even a single unified definition of what constitutes a heatwave. Like him, other experts not directly involved in the discussion want to keep the focus on the wider risk management programmes.

“Even if one does argue for naming heatwaves, it can only be a small part of a wide range of preparedness activities,” says Singh, who calls for a focus on longer-term heat adaptation. “These are systemic changes, and tinkering with names of heatwaves seems almost like a distraction from the real problems and solutions. Unequal societies heat and cool unequally. Addressing this is the crux.”

English (US)

English (US)