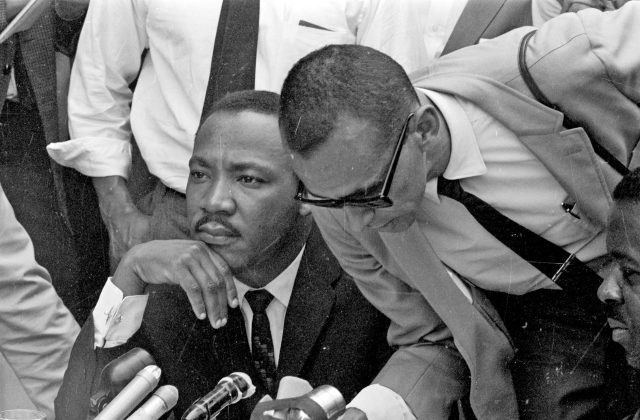

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., left, and Pastor Wyatt Tee Walker at a press conference at the A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham, AL on May 10, 1963. (Alabama Department Of Archives And History. Donated By Alabama Media Group. Photo By Tom Self, Birmingham News)

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., left, and Pastor Wyatt Tee Walker at a press conference at the A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham, AL on May 10, 1963. (Alabama Department Of Archives And History. Donated By Alabama Media Group. Photo By Tom Self, Birmingham News)By Barnett Wright | The Birmingham Times

In the solace of a Birmingham jail in April 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. penned what many consider “one of the greatest documents ever written by an American.”

King came across an article in the afternoon edition of The Birmingham News headlined “White Clergymen Urge Local Negroes to Withdraw from Demonstrations.” That inspired the Civil Rights giant to craft a jewel of American literature — “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

The City of Birmingham and the nation observe King’s birthday on Monday, January 20 and more than 60 years later, his heartfelt letter is considered the preeminent document of the Civil Rights movement, appearing in hundreds of anthologies and designated as required reading for many students worldwide. It has been translated into more than 40 languages.

Clayborne Carson

Clayborne Carson“King initially intended the Birmingham letter as a response to the eight clergymen, but it became the most cogent and influential defense of nonviolent resistance ever written,” said Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

Barry McNealy, Historical Content Expert at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI), said the letter is “one of the greatest documents ever written by an American … on par with the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address,” McNealy said. “The ideals that were contained in it completed the rhetorical journey that was set out by Thomas Jefferson and continued by Abraham Lincoln … “

Both the Gettysburg Address and the Declaration of Independence share a theme of freedom as the ultimate goal and emphasize the fundamental importance of individual liberty and the pursuit of happiness as guiding principles in the United States.

In his “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” King connects with those ideas by writing, “We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom.”

Written Without Notes

King’s response was even more impressive because it was written without notes or other reference materials, say historians.

Jonathan Rieder

Jonathan RiederJonathan Rieder, a professor at Barnard College and Columbia University and author of “Gospel of Freedom: Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and the Struggle That Changed a Nation,” said King composed the letter “like a painter, like a sculptor.”

“His ability to draw fragments together into these always-new compositions and permutations was part of his artistic brilliance,” Reider said. “Forget about whatever intellectual and spiritual brilliance went into it. To me, what is extraordinary is that he does it without notes. It’s all deep in his soul and his spirit.”

McNealy said the letter was telling for another reason.

“[It] says more about the nation and the people who challenged Dr. King’s academic prowess, who challenged his intellectual level and said that he didn’t earn any of his credentials that he worked for other the years,” said McNealy.

And King’s scholarly letter remains relevant because some of the same arguments made against King then were made against Vice President Kamala Harris who ran unsuccessfully for U.S. President in 2024, the historian said.

Barry McNealy

Barry McNealy“When you think on a present-day level one of the things that was dropped on Vice-President Harris repeatedly was how she couldn’t answer a question and how unintelligent she was; and she graduated with honors from Howard University and became a lawyer and a state attorney general,” McNealy said. “This is a tired trope that has been used about Black people and people of color, marginalized people since the very beginning.”

He added, “So when we think about [King] sitting in that cell with nothing but his experience and his education that he garnered up to that point in his life and he creates a document like that without any type of assistance, not even a dictionary it shatters that myth that marginalized people are less when it comes to intellectualism in academia.”

‘My Dear Fellow Clergymen’

King and others were arrested on Friday, April 12, 1963, for violating a court injunction prohibiting Civil Rights demonstrations in the city. He was released eight days later, and April 16 is the date placed on “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

King and others were arrested on Friday, April 12, 1963, for violating a court injunction prohibiting Civil Rights demonstrations in the city. He was released eight days later, and April 16 is the date placed on “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

The clergymen were critical of “outsiders” who were leading protests in segregated Birmingham. The clergy called the demonstrations “unwise and untimely.”

King’s response began: “My Dear Fellow Clergymen. While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities ‘unwise and untimely.’ Seldom do I pause to answer criticisms of my work and ideas.”

King wrote on scraps of writing paper supplied by a Black jail trusty and yellow notepads surreptitiously brought into the jail by his attorneys, said Stanford’s Carson.

“Under these difficult circumstances, King drafted the most crucial public statement of his career, benefiting from the fact that he had been preparing for many years to write such a statement,” Carson said.

King was intentional about addressing the clergymen who were standing on the sidelines, McNealy said.

“You had people that were vociferous in terms of their white supremacy and their racism like [Alabama governor] George Wallace or [Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner] Bull Connor … you had those people, but you also had the people who were cowed by them … Dr. King was talking to those people who were on the fence, who knew right from wrong but they were afraid to act on it. He started criticizing them for hiding behind the stained-glass windows.”

Columbia’s Rieder said the letter is from a man who is concerned about his own people but at the same time has great love for humanity.

“He speaks to all oppressed people, and that’s his basic Christian concern,” Rieder said, “That’s why he’s upset about the appalling silence of the good people.”

Some things haven’t changed more than 60 years later, McNealy said.

“When you think about Dr. King, he said the minute that you refuse to speak towards injustice you begin to die. In other words, living a lie is poison. It doesn’t necessarily poison your body, it poisons your spirit, it poisons your soul and everything you do from that moment when you compromise, you don’t stand up to the truth, everything you do is a spiral down. And this is what he was trying to get people to see.”

Document Never Sent

Jonathan Bass

Jonathan BassSamford University history professor S. Jonathan Bass said King gave bits and pieces of the letter to his lawyers to take back to movement headquarters, where the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, King’s top assistant, began compiling and editing the material, Bass explained. The final version was dated April 16, 1963.

The 21-page, typed, double-spaced “Letter” appears as though it is personal correspondence addressed to the eight white ministers, Bass said. The document was never sent to them, however, which led some to question whether the letter was intended for the clergymen.

“King and Walker had discussed writing a jailhouse epistle while in Albany, Ga., in 1962,” said Bass, who wrote “Blessed are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders, and the Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

“In addition, King had previously preached a sermon entitled ‘Paul’s Letter to Christians in America.’ This was something they wanted to do, but the occasion never presented itself until Birmingham.”

The white ministers were the perfect symbolic audience for the letter, Bass said. “After all, the Apostle Paul wrote letters from jail to fellow believers. On the surface, the letter is a public relations document. It served as the symbolic finale to the Birmingham movement when it was published by the media beginning in May 1963.”

From left, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy hold a press conference at the A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham, on May 10, 1963. (Alabama Department Of Archives And History. Donated By Alabama Media Group. Photo By Tom Self, Birmingham News)

From left, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy hold a press conference at the A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham, on May 10, 1963. (Alabama Department Of Archives And History. Donated By Alabama Media Group. Photo By Tom Self, Birmingham News)‘Warrior Spirit’

Rieder believes the letter may have been tweaked after King’s release from jail, but the words are heartfelt.

“King was so exasperated by these preachers. These eight white clergymen, they embodied everything that had been building up with him for years with white moderates,” Rieder said.

King’s anger at the moderates who said “go slow” was rising. King “was depressed; he was in a panic,” Rieder said. “He had this terrible time in solitary. He reads this [newspaper article], and they are telling him to ‘wait,’ and suddenly his indignation just pushes him out of that depression. It’s like he got his warrior spirit back.”

Another brilliant aspect of the letter, according to historians, is the multitude of perspectives that King brings to his response.

“He expressed empathy with the lives of millions over eons and with the life of a particular child at a single moment,” writes Taylor Branch in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Parting the Waters, America in the King Years, 1954-63.”

“He tried to look not only at white preachers through the eyes of Negroes but also at Negroes through the eyes of white preachers. By degrees, King established a kind of universal voice, beyond time, beyond race,” Branch writes. “As both humble prisoner and mighty prophet, as father, harried traveler, and concerned leader, he projected a character of nearly unassailable breadth.”

1 week ago

2

1 week ago

2

English (US)

English (US)